The history of Dog Eating

Facts about dogs as meat suppliers

For many years, the dog has not just been a dog for us, but has become a family member, a friend, a comforter or even a therapist and has become an indispensable "social lubricant" in this country. Sometimes the owners spend immense amounts of money on their four-legged friends, sometimes the love for dogs perverts in all imaginable forms. However, this was not always the case, and the times when dogs were used as a source of meat in Germany and slaughtered for their meat were not that long ago.

What hardly anyone knows: in Germany, too, dogs were killed in state-controlled slaughterhouses until almost four decades ago. It was not until 1986 that the killing of dogs and cats for meat was banned by law. The taste for dog meat does not only extend to Asia, as in some cantons of Switzerland, people still like to eat dogs meat. In general, the rule is: where there is no close human-dog relationship, normally no barriers exist that protect Canis Lupus Familiaris from hunting for its meat. But let’s take a quick look at the history of dog eating. Very soft minds should consider at this point whether they really want to deal with this topic.

Preface

It's no secret that Asians eat dogs and cats. Cantonese, it is said, will eat anything with four legs except tables, and eat anything with wings except airplanes. What is mostly unknown, however, is that roast dog is by no means an everyday dish in Asia, but that dog meat is quite expensive and is only eaten on special occasions. Eating a dog is a social event that often takes place in a larger group. Countries where dogs are eaten include: Korea, Vietnam, China, the Philippines and some Central and South America.

In Africa the matter is somewhat mixed, areas where dogs are eaten alternate with areas whose inhabitants consider eating dogs as abhorrent as we do and consider their dog-eating neighbors to be primitive barbarians.

But the tradition of eating dogs is still maintained in Western Europe, especially in the rural areas of Switzerland and Austria, as well as in Belgium and France, where dogs are served discreetly on request in certain gourmet restaurants. Dogs and cats are still eaten in parts of Spain these days.

In Germany, the consumption of dogs and cats is prohibited by law, but this is only the legal sanction of a taboo that is already generally recognized in society. This means that every breach of this ban also represents a dramatic cultural violation, which essentially results in the person concerned being excluded from civilization. For us, anyone who eats dogs is no longer human! For us, cynophagy (= eating dogs) is almost an act of cannibalism and represents an anticipated breach of the strongest food taboo we know here.

Before 1986, anyone in Germany could legally slaughter dogs, including their own. In addition to meat, dog fat was particularly popular because it was known to be an effective medicine against respiratory diseases and there was actually evidence of a tuberculostatic effect. These slaughters by no means took place in a lawless context, but were expressly permitted until 1986 as long as express regulations were adhered to. The owner had to prove in advance that the animal was legally purchased and had to pay the slaughter fee. The slaughter itself took place in separate rooms within the slaughterhouse - for epidemic hygiene reasons - as did the mandatory meat inspection.

The dog fat and meat were sold in both legal and illegal markets. There were black markets in many cities, for example in Hamburg in the Schanzenviertel there was an illegal dog market called “Fido”. By the way, dog fat was also available in pharmacies until 1986, but was always sold out due to the high demand.

Dog slaughter was very controversial in public since the 1950s at the latest, but it still took three decades until it was finally banned. In fact, little was done, especially by the CDU (a German party), to prevent the beloved four-legged friends from being eaten. However, this inaction was based on legitimate legal doubts, which will be discussed later.

Eating dogs

While it was normal for a "poor" medieval family to have fresh meat on the table at least three times a week, from the age of industrialization onwards, workers could only dream of such conditions. The bourgeois soup kitchen made eating meat an absolute rarity. In the search for inexpensive meat that would give the hard-working men the strength they needed, firstly they turned to horse meat. This was very popular with our Germanic ancestors and was considered a delicacy. Horses (particularly the gray ones) were sacred, and their meat was ritually eaten on special occasions. The Catholic Church put a stop to this from the 8th century onwards in an attempt to eradicate everything pagan with fire and sword. From then on, horse meat was considered outlawed and eating it was forbidden. The church-imposed prejudices against horse meat were still strongly represented in the population even after more than 1000 years, and only sheer necessity allowed it to become an accepted food. However, this was not the final solution, especially because horses were expensive and raising and maintaining them cost a lot of time and money. The horse was simply too precious to be eaten by the poor. So an even better idea was needed.

And so the dog was discovered: a good feeder, easy to keep and breed and - apart from hunting dogs and guard dogs - absolutely useless, because the city's stray dogs meant little to the citizens and were more of a nuisance to them. The fashion for keeping dogs as companions and strolling down the streets with them only emerged slowly. So the dog was chosen, and its meat was heavily promoted, since taboos and prejudices against eating dogs (like horses) were set very deep in the population. Dog meat should therefore be considered a cheap alternative to pork or beef. Dog butchers gradually emerged in the second half of the 19th century and were able to source both strays and bred or stolen dogs for meat. Nevertheless, it must be said that the poor population really only ate dogs and cats in times of dire need. This involuntary diet was immediately discontinued as soon as times changed. How little dog meat was valued can also be seen in the criminal records: if a butcher in the Middle Ages was caught selling dog meat to his unsuspecting customers, it cost him his head, as the medieval guild regulations required him to carry out his craft properly and properly pursued in an honest way. The industrialized bourgeoisie lacked such idealism and stubbornly refused to introduce an obligation to label dog meat in butcher shops. Labeling dog meat as dog meat was only made legal by the NSDAP in 1937 and was urgently required, as many frauds involving dog meat in restaurants and slaughterhouses had been documented up to that point.

Promoted by social misery, dog slaughter became widespread in the working-class areas of cities and in slums, particularly in Silesia, Thuringia, Bavaria, Württemberg, Brandenburg and Berlin. The old belief in the effectiveness of dog fat against respiratory diseases also contributed to the spread of dog meat as food. Dog fat (Adeps Canis) has been used for centuries in folk medicine to treat human and livestock diseases. This fat could be purchased from so-called vase masters, who were responsible for removing animal carcasses. The fat was consumed pure, eaten with bread or mixed with meals. Because of the healing powers of dog fat for respiratory diseases, it was particularly widespread in areas where there was a lot of mining, glass industry or other industries that were hazardous to the lungs. In the long term, the medicinal use also resulted in the use of dog meat in the affected areas.

The dogs, which were primarily used for food, were either bred for slaughter - or strays were picked up. In many neighborhoods, smelly shacks or kennels were built in the narrow backyards in which the dogs were fattened. Keeping dogs as we know them today was unknown and not possible back then. As an omnivore, the urban stray was a direct competitor to humans for food; Dog ownership itself was a luxury that only wealthy citizens could afford. However, this brings us directly to another way dogs were obtained: the dogs were stolen. Wealthy city dwellers who could afford to feed a dog were particularly affected. This type of meat procurement gradually became a problem in the cities, so that many parts of the city became disreputable and were avoided by dog owners, such as the weaving colonies around Potsdam. Reports rained down, but for the victims of the kidnapping, any help usually came too late. Therefore, there were many demands that all dogs intended for slaughter be presented to the authorities alive and with a tax stamp.

The butcher paid the dogcatcher the slaughter weight of the dead dog, regardless of whether it was a pedigree dog or a stray. Animals brought alive therefore cost between one and three marks. No breed of dog was preferred over the other for taste reasons. It's completely different in Asia: here, the Chow Chow was bred specifically as a tasty dog breed for use in the kitchen. By the way, it is a fact that dog butchers bought dogs without asking about their origin. This gave rise to a new and lucrative industry, namely dog kidnapping: a wealthy animal lover's dog was stolen, and a ransom was extorted. Since the pedigree dogs often cost several hundred marks, which was really a lot of money at the time, the owner was usually prepared to pay the "finder's fee".

At the end of the 19th century, stolen dogs were also offered in Munich at the official dog market, which took place on Sundays and public holidays at the Viktualienmarkt. After these conditions became known, the market was closed several times, so that buyers and sellers began to meet "privately" - for example in the "Dog Exchange" association, which met in the "Oberotti" inn at Sendelfingerstrasse 55. From 1920 onwards, a rabbit and dog market was held regularly in the "Braunauer Hof" at Frauenstrasse 3, and from 1927 onwards it took place at the "Schweizerwirt" at Tegernseer Landstrasse 64. Dogs were still slaughtered here in 1951 and the picture mentions the restaurant in 1954 as a transshipment point for slaughter dogs.

The places where the slaughter took place were originally anything but hygienic and due to the whining of the still living animals and the smelly waste, they increasingly became a public nuisance. Control of hygienic conditions fell by the wayside almost everywhere, despite state inspectors. But since dog meat played an important role, especially in the poor parts of the population, no one came up with the idea of calling for a general ban on the slaughter of dogs and cats. The idea of protecting dogs as a special animal would have seemed downright absurd to people at the time. The main aim here was to establish a justifiable legal framework for dog slaughter. The aim was to remove the killing of animals and their processing from public life in cities, since before slaughterhouses were built, animals were slaughtered on streets and squares for everyone to see. Therefore, all German states introduced mandatory slaughterhouses for commercial dog slaughter by the turn of the century. The fee for this was around 50 Pfennigs and proof of legal acquisition of the animal had to be provided. Despite the official requirement to provide proof of ownership, there were enough butchers who would slaughter any dog for a little change or part of the meat without asking for a tax stamp or birth certificate. It is estimated that for every dog legally slaughtered, there were three illegal slaughters.

By the way, in 1982 (!) the price for dog meat and horse meat in Munich and Dresden was 50 Pfennigs per kilo, while beef and pork cost 1.24 to 1.52 Marks. Due to the attractive price, dog meat was sold throughout Germany, but some areas stood out in particular. The dog was often eaten in the pan, especially in southern Germany, Silesia, Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg. Munich in particular was considered one of the strongholds of dog eaters in the German Empire, and it was known beyond its borders that the city was very fond of dogs in terms of culinary delights. In 1892, the French "Internationale Fleischerzeitung" (international butcher's magazine) wrote that "Munich, the art and festival city, was already being declared a dog city."

Man bettelt, borgt, hungert

und schlachtet fette Hunde, die man sich auf

eine höchst wohlfeile Art zu verschaffen weiß.

(You beg, you borrow, you starve

and slaughters fat dogs that people eat

a very cheap way to procure.)

A. von Schaden 1835: “München, wie es trinkt und ißt" (Munich, how it drinks and eats)

The slaughter itself, as well as the consumption of dog meat, was subject to the economic situation. Due to poor supply, dog meat consumption increased significantly during World War I, as well as during the Great Depression and the inflationary period of 1923, where it reached its peak. In the vintage book “Bei mir - Berlin” (With me - Berlin!) the author wrote in 1923: "In the first half of September, 13 new dog slaughterhouses were added to the already existing 32 dog slaughterhouses in Berlin. Even under the old system (in the imperial era, author's note) dog meat was consumed, but only in some of them few cottage industry villages in the poorest region of Germany, in the Saxon Ore Mountains, and neither in Berlin nor in any other big city, and today this dog meat - for Sunday - is bought by members of the educated former middle class."

Adeps Canis- dog fat as medicine

During the Second World War, necessity drove people back to the dog butcher. But even after the war, there was unity in both German states, because dogs were slaughtered in both. While before the war there was a uniform reporting requirement and statistics about the dog slaughters carried out, after the war no one showed much interest in recording the numbers, which is why there are only incomplete figures about the number of dogs culled. Nevertheless, the previous centers of dog slaughter remained true to each other, so that outside the GDR - especially in Munich and Augsburg - there was a similarly high number of slaughters inspected as before the war. Here, too, it can be assumed that for every official slaughter there were three to four illegal slaughters. The last slaughters took place in Hamburg in 1954, while dog slaughters were carried out in Munich until 1985, although here the reason for this is more likely to be culinary than out of sheer necessity.

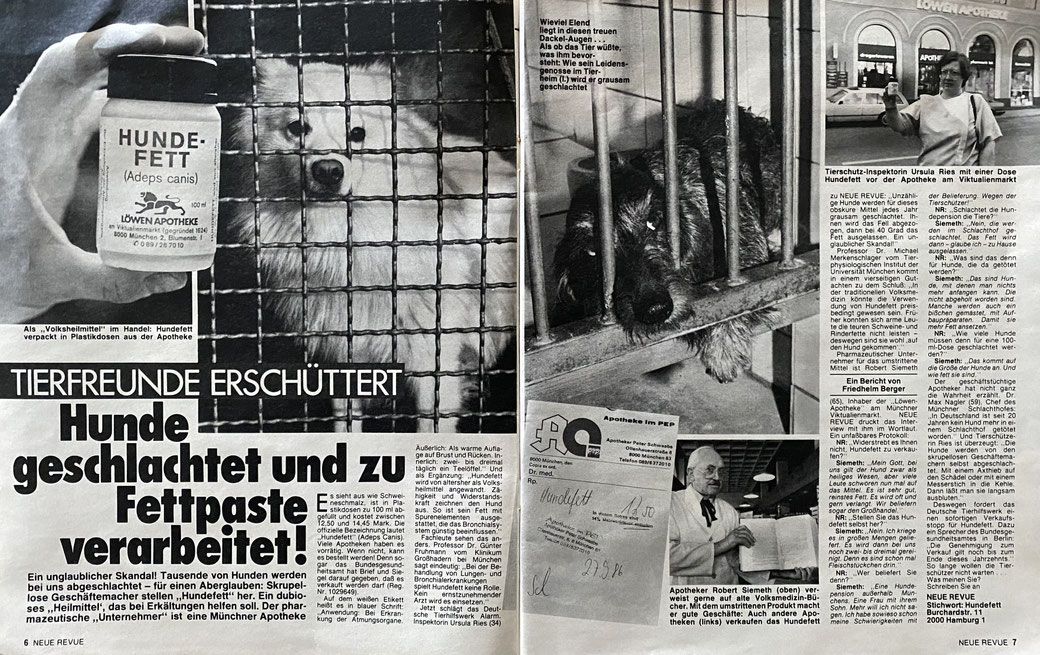

Due to the increasing prosperity of the population, dog meat became increasingly less interesting and the medical aspect came to the fore. Dog fat - Adeps Canis - was in demand and was said to have great healing properties, especially for bronchial diseases. Anyone who didn't get it from acquaintances who slaughtered it themselves or on the black market literally had to pay a pharmacist's price for it. Dog's fat was registered in Bonn under the registration number 1029849 until 1989. It could be used both externally as a rub and internally. The license for Adeps Canis expired in 1989 with the German Federal Health Office.

Due to the high demand, dog fat was a very lucrative product, from which both the pharmacist and the owner of the slaughter dog could make a considerable profit. In Munich, around 1956, pharmacies paid around 12 DM per kilogram of dog fat in order to then sell the dog fat for the hefty price of around 14.50 DM per 100 ml. The pharmacists were therefore described by quite a few animal lovers as unscrupulous profiteers and dog murderers.

Dog leather - a new fashion folly?

"As an illustrated magazine reports, dog leather is said to be processed in Paris for shoes, gloves and handbags. A tannery supposedly supplies 15,000 dog skins a year. The leather is said to be suitable for people with wet hands. A pair of shoes is said to cost 80–110 DM. The increasing sales currently amount to 1,000 pairs per month. Shepherd dogs would give the best fur, while poodle fur would be unsuitable. The fact that something like this can happen is due to the fact that dogs are no longer allowed to be buried in France. They are coming to the cladding shop: the meat is processed into feed, the fat into soap production and the fur into luxury leather.

The situation is difficult for us too, how few dog cemeteries we have, how difficult it is to find a place for a grave - for example in a friend's garden - but then the grave still has to be dug.

It is a terrible thought for us that the remains of man's best friend, the housemate we see as a family member, should be processed like this after his death. That is why the idea of dog cemeteries must be promoted more and more in cooperation with animal protection associations.

How long will it take until this "Création" from the fashion headquarters until this "dernier cris" - this latest craze in fashion - is imported into Germany - and until business-minded people see their profit here and produce these dog leather items themselves and bring them onto the market? Dog catching would become a profitable business for thieves. Ethos? Idealism? Of course, things like that still exist, even if they are rare. Especially if you want something chic. So it's time to prevent, to wake up and to point out the evil that lies in wearing a glove made from the skin of a dog that you may have recently petted. Only by outlawing the mere thought - even before you have started importing or even producing - can you help. And the best helpers have to be the women, who love the dogs so much - and pamper them. You could be offered dog leather bags. If you reject it indignantly, report a business that will offer it. Now it's still time to call out unreservedly here, because there is no "business damage" yet, as the article does not yet exist in Germany. Help us, especially our ladies, so that he never shows up!"

Source: "The German Spitz", No. 40, page 27

The ban on dog slaughter

After the war, the economic situation in this country improved much faster than expected, and the number of dog slaughters consequently fell again. Nevertheless, there were few reservations about the slaughter itself, apart from isolated moral concerns here and there. However, since the beginning of the 1950s, animal welfare associations have increasingly taken issue with this and denounced "dog murder" in public. The press and political parties gradually joined in and a broad alliance emerged for a ban on the slaughter of dogs and cats. After the Bild newspaper became involved in the issue in 1954, the effectiveness of this alliance increased, but it would still be three decades before the slaughter was finally banned.

The discussion about the slaughter ban meant that anyone who ate dogs or used their fat for pharmaceutical purposes was now considered barbarians or cannibals. As a result, virtually no one who had fewer problems with the slaughter could publicly comment on it. German chancellor Konrad Adenauer is quoted as saying: "I could only lose the majority if a newspaper wrote that I slaughter dogs." The sometimes sensational and nonobjective reporting made it absolutely impossible for opponents of the slaughter ban to take a public position, while the public was sensitized accordingly. Now the law just had to be formulated and passed. Surprisingly, however, the first attempt at a ban was rejected on the grounds that "there is no general slaughter ban for any animal species in Germany”. There is no objective justification for the ban and, moreover, the ban on slaughter would make the legally required protection of dogs much more difficult, as it must be assumed that consumers would then procure the dogs they need illegally.

In principle, under civil law, any animal can be slaughtered for a reasonable reason, as long as the slaughter takes place in accordance with existing regulations (animal protection laws, etc.). A ban on the slaughter of animals is only permissible for health and hygiene reasons, which means that the animal must pose a specific danger to slaughter personnel and consumers in order for an effective ban to be imposed. One example is the monkey, whose slaughter for consumption is prohibited because contact with the blood and organs of monkeys can cause serious illnesses in humans (including Marburg infection). The import ban on monkey meat took place here in 1973 and the ban on slaughter took place in 1980 after several fatal infections. So why did people speak out against a ban - at least for now? The government defended the time-honored principle that any animal could be used for reasonable reasons. It was felt that a ban on the slaughter of dogs would set a precedent for other domestic animals, such as horses, rabbits, etc.

The ban on the slaughter of dogs and cats enacted in 1986 was ultimately cobbled together and engineered: when the Meat Inspection Act was amended, the Bundesgesundheitsamt (Federal Health Office) named eight possible pathogens that played a role in infections caused by dog and cat meat. This was in no way a novelty, but simply a list of well-known facts from which no greater health risk emerged than the consumption of, for example, beef or pork. Due to the poor arguments, the Bundesgesundheitsamt added the points "drug residues" (from hormone injections or through flea collars) and "environmental contamination" (lead from canned food) in order to be able to derive the following formulation: "Overall, the slaughter of Dogs and cats... pose risks to human health. This affects both slaughter personnel and consumers." Based on this statement, the Bundesernährungsministerium (Federal Ministry of Food) concluded that the health risks mentioned were due to close contact between people and dogs or cats. This meant that the ban on slaughter could be justified on hygienic reasons. Since then, the Fleischhygienegesetz (meat hygiene law) of February 1987 states: "Meat from monkeys, dogs and cats may no longer be obtained for human consumption." From this point on, Germany finally returned to the bosom of civilization for animal rights activists, pet owners and the media - except in the sector of their use as laboratory animals, which is still the largest bloodletting of the dog population.

A question of morality

The question that heated up people's minds at the time was: "What is the dog?" A faithful companion, close to people and useful, but also food and medicine? So a farm animal, like a cow, nothing more and nothing less? Or is it a special animal, elevated by its proximity to humans, distinguished by its nature and characteristics as an animal worthy of protection with a special status? Today this question seems absurd, but back then the topic was discussed seriously. Weren't horses also useful and very docile animals, whose meat was still tasty? So why exclude the dog as long as existing animal welfare laws were adhered to during slaughter? The mere ethical rejection seemed far-fetched to many people at the time. Although the majority of people at that time no longer wanted to eat dogs at all - meat was tainted with the stigma of poverty - people had no objections to those who were inclined to meat or fat, they simply didn't care about it. In Switzerland, this topic is still handled in this way today: people love and respect dogs, they are prepared to invest a lot of money in them, but what the citizen ultimately does with his "investment" - i.e. whether he keeps it as a pet, sells it or not eats - is absolutely none of the state's business, at least as long as everything takes place within the framework of animal welfare regulations. Well, what's right here, what's wrong?

Although the slaughter ban took a long time to come, it finally came with full consequences. The ban on dog slaughter underlines the extraordinary role that we Germans attach to our dogs.

And deservedly so! The story of the dog is part of the history of mankind. The dog faithfully stood by the man and shared the fight and work with the two-legged companion, giving him his own strength. Of all animals, the dog was chosen to play a significant role in the reclamation of entire habitats. Without dogs there can be no human development, without guardians there can be no property, without herders there can be no livestock farming, etc. Therefore, the dog rightly stands above all other domestic animals, and we rightly turn away in deep disgust when it comes to dog eating. The ancient Germanic tribes, as well as the ancient Egyptians and the Assyrians, respected the dog so highly that its consumption was absolutely taboo there. And thousands of years ago, peoples or tribes who indulged in dog eating were perceived as being more or less in a state of barbarism. Or to follow Bernardine de St. Pierre, who stated in his "Études de la nature" (1784) "that eating dogs was the first step towards cannibalism".

And I absolutely agree with that!

[1] www.wochenblatt.de/archiv/als-hierzulande-hund-noch-auf-dem-speisezettel-stand-174321

Rüdiger von Chamier - "Hunde essen, Hunde lieben: Die Tabugeschichte des Hundeverzehrs und das erstaunliche Kapitel deutscher Hundeliebe" (Eat dogs, love dogs: The taboo of dog consumption and the amazing chapter of German dog love)

09.01.2024